Difference between revisions of "Robert Mapplethorpe"

| Line 38: | Line 38: | ||

* [[LGBTQ Photographers]] | * [[LGBTQ Photographers]] | ||

| + | * [[LGBTQ Founders and Executives with Charitable Foundations]] | ||

==Further Research/Reading== | ==Further Research/Reading== | ||

| Line 43: | Line 44: | ||

* http://www.mapplethorpe.org/ | * http://www.mapplethorpe.org/ | ||

* http://www.guggenheim.org/new-york/collections/collection-online/artists/bios/1391 | * http://www.guggenheim.org/new-york/collections/collection-online/artists/bios/1391 | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Revision as of 14:44, 30 July 2017

Country

United States

Birth - Death

1946 - 1989

Occupation

Photographer

Description

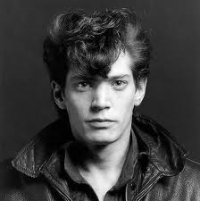

Robert Mapplethorpe was a controversial black & white portrait and scenic photographer whose often homoerotic work sparked a national and international debate on the issue of public funding for the arts. This issue lead to further debates about censorship, freedom of speech, and the definition of pornography in the public realm.

Mapplethorpe studied drawing, painting, and sculpture at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York but dropped out before obtaining his degree. He was attracted to photography and its use in creating collages as an art form. At first, Mapplethorpe used Polaroids in his artwork before moving to fully developed film.

His work from the beginning centred on portraits, particularly of minor celebrities that were in his circle of friends. As he grew more confident, he pushed the boundaries of his subject matter’s appearance and behaviour, encompassing nudes and the documenting of the underground S&M scene. Although this subject matter may be considered controversial, the style and context of the photographs were considered remarkable for their technical and formal mastery.

Mapplethorpe’s images increasingly challenged standard references of classic photographic content, encompassing compositions of male and female nudes alone and together, utilizing different techniques and formats (such as 20” x 24” Polaroids; prints on linen; and dye transfer colour prints) that established new artistic parameters for the art of photography. In all of his work, he was regarded as presenting new and unexplored subject matter that was considered high art and devoid of political agenda. Mapplethorpe concentrated purely on the subject matter at hand rather than their political or social meaning.

His traveling solo exhibition of 1989 entitled The Perfect Moment generated huge public controversy and raised the issue of public funding for the arts. As described by Mapplethorpe, the artistic point of the photographs was to reject the notion of gay male sexuality as diseased as reflected with the stigma of AIDS. The show was curated by the Institute of Contemporary Art in Washington D.C.

Certain members of the U.S. Congress and several right-wing conservative organizations objected to the content of this show, which had obtained some public funding. When the Corcoran withdrew the show, there was a cry of censorship and political interference from the art world. A major benefactor to the Corcoran withdrew his financial support. These actions sparked a national debate on the issue, and Mapplethorpe became a cause-celebre on both sides of a cultural war. The process was repeated in 1998 when a book of Mapplethorpe’s work was confiscated and banned.

In the interim, Mapplethorpe was diagnosed with AIDS. Prior to his death, he established the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation to promote photography museums and to fund research in the fight against AIDS.

Mapplethorpe had a long term relationship with art curator Samuel J. Wagstaff Jr.

It is coincident that his most revered images depict the dangerous world of sex, and he himself succumbed to the most dangerous disease that such a world was transmitting. Mapplethorpe pushed the boundaries in his photographs as well as in his personal lifestyle, and was made to suffer the consequences of each.

To what extent does an artist who receives public funding need to put constraints on their artistic output based on that same public’s taste and definition of moral acceptability? Art is often breaking new boundaries and challenging the normative politics of a time or generation, putting the artist in the spotlight as a renegade or outlaw. We see this time and again throughout history. In Mapplethorpe’s case, he took the emerging underground world of gay sex together with the emerging fear of the AIDS epidemic as his subject matter and boldly made them visible. Today, we can view such artistic pieces in a calmer and more pleasurable perspective as representative of a specific period in time – and a developing cultural initiative. Perhaps this is the answer to the question – allowing the passage of time to dictate the acceptance and value of the risky pursuit of investing in the arts.