Difference between revisions of "Louis Sullivan"

| (3 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

==Description== | ==Description== | ||

| − | + | Louis Sullivan was one of the most creative and influential architects of all time. As a product of a generation which witnessed the creation of the modern urban city, his architectural designs for buildings and homes were in constant demand. Rather than build out, Sullivan decided to build up. Sullivan is considered America’s first modern architect. | |

| + | |||

| + | Sullivan’s talent for drawing was recognized at an early age when he entered the school of architecture of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology at 16. After one year of study he began practising as a professional architect in Philadelphia. | ||

| + | |||

| + | After Chicago’s great fire decimated the city in 1873, Sullivan moved there for work. He also spent a year studying at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris before teaming up with fellow architect Danhmar Adler to create Adler and Sullivan. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The development of inexpensive and mass produced steel at the time, in part due to the mass construction of railroads, allowed its use for constructing buildings of ever greater height. It was in Chicago, and under the aegis of Louis Sullivan, that the use of steel to build a new style of high-rise building evolved. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Louis Sullivan is particularly noted for developing unique architectural elements that allowed a building to be constructed higher and larger. Each of his buildings had three components: a base on which the weight of the building could be sustained, a shaft or column with which the building rose, and a crown or cornice at the top of the building. From this concept came his most famous saying: form follows function. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The other unique element that Louis Sullivan could now incorporate was aesthetic design. Because steel could be manipulated into various designs while retaining its strength, Sullivan was able to construct buildings with a design that thrilled and enthralled the public. For example, the signature of his buildings became the green steel canopies at the entrance of many of his landmark buildings. His buildings became a mix of geometry and elaborate ornamentation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | With the financial panic of 1893, business for Adler and Sullivan dried up. The firm was dissolved in 1895 after Adler quit, much to the angry dismay of Sullivan. Sullivan went through a period of deep personal depression and his opportunities and output declined through the remainder of his life. Nevertheless, his contributions to architecture, design, and the creation of the modern building had been made. Sullivan’s substantial work that remains today is considered the most treasured pieces of historical architecture in the United States. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Louis Sullivan was an intensely private man and he was noted for his guarded and private personality. As with many LGBTQ individuals of his era, his personal correspondence was destroyed toward the end of his lifetime. His biographer, Robert Twombly, in his extensive book Lous Sullivan: His Life and Work (1986), notes Sullivan’s preference for the company of men, his study of the male anatomy, his close mentorship with other male architects, his brief but disastrous marriage, and his personal correspondence with other males . At a young age, Louis Sullivan was noted for his romantic notions, his distinct swagger, and his smart dress. Twombly concludes that there is little doubt as to his homosexuality, while also acknowledging no direct confirmation of such from Sullivan himself. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The final years of Louis Sullivan’s life is noted for his increasing reclusive nature and estrangement from friends and family. He was forced to sell much of his personal belongings to support himself, and he began to reside in ever-cheaper hotels to economize his personal expenditures. At this time, he completed his Autobiography of an Idea in 1924, the year of his death. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The American Institute of Architects posthumously awarded Louis Sullivan its prestigious Gold Medal in 1946. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Louis Sullivan’s life is an odd story of a hero. While his artistic output displayed his unique talents in design, ornamentation, and architectural structure, his lifestyle and noted caustic personality reflected his acute sensitivity to layers of personal suffering, both professionally and financially. How much of this could be attributed to his suppressed homosexuality can only be answered by the man himself, but it is a scenario often played out by LGBTQ individuals in an intolerant society every day. | ||

| + | |||

==See Also== | ==See Also== | ||

Latest revision as of 13:50, 6 May 2015

Country

United States

Birth - Death

1856 - 1924

Occupation

Architect

Description

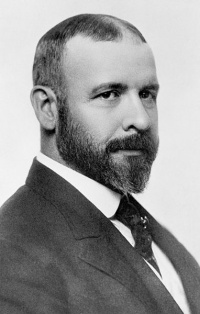

Louis Sullivan was one of the most creative and influential architects of all time. As a product of a generation which witnessed the creation of the modern urban city, his architectural designs for buildings and homes were in constant demand. Rather than build out, Sullivan decided to build up. Sullivan is considered America’s first modern architect.

Sullivan’s talent for drawing was recognized at an early age when he entered the school of architecture of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology at 16. After one year of study he began practising as a professional architect in Philadelphia.

After Chicago’s great fire decimated the city in 1873, Sullivan moved there for work. He also spent a year studying at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris before teaming up with fellow architect Danhmar Adler to create Adler and Sullivan.

The development of inexpensive and mass produced steel at the time, in part due to the mass construction of railroads, allowed its use for constructing buildings of ever greater height. It was in Chicago, and under the aegis of Louis Sullivan, that the use of steel to build a new style of high-rise building evolved.

Louis Sullivan is particularly noted for developing unique architectural elements that allowed a building to be constructed higher and larger. Each of his buildings had three components: a base on which the weight of the building could be sustained, a shaft or column with which the building rose, and a crown or cornice at the top of the building. From this concept came his most famous saying: form follows function.

The other unique element that Louis Sullivan could now incorporate was aesthetic design. Because steel could be manipulated into various designs while retaining its strength, Sullivan was able to construct buildings with a design that thrilled and enthralled the public. For example, the signature of his buildings became the green steel canopies at the entrance of many of his landmark buildings. His buildings became a mix of geometry and elaborate ornamentation.

With the financial panic of 1893, business for Adler and Sullivan dried up. The firm was dissolved in 1895 after Adler quit, much to the angry dismay of Sullivan. Sullivan went through a period of deep personal depression and his opportunities and output declined through the remainder of his life. Nevertheless, his contributions to architecture, design, and the creation of the modern building had been made. Sullivan’s substantial work that remains today is considered the most treasured pieces of historical architecture in the United States.

Louis Sullivan was an intensely private man and he was noted for his guarded and private personality. As with many LGBTQ individuals of his era, his personal correspondence was destroyed toward the end of his lifetime. His biographer, Robert Twombly, in his extensive book Lous Sullivan: His Life and Work (1986), notes Sullivan’s preference for the company of men, his study of the male anatomy, his close mentorship with other male architects, his brief but disastrous marriage, and his personal correspondence with other males . At a young age, Louis Sullivan was noted for his romantic notions, his distinct swagger, and his smart dress. Twombly concludes that there is little doubt as to his homosexuality, while also acknowledging no direct confirmation of such from Sullivan himself.

The final years of Louis Sullivan’s life is noted for his increasing reclusive nature and estrangement from friends and family. He was forced to sell much of his personal belongings to support himself, and he began to reside in ever-cheaper hotels to economize his personal expenditures. At this time, he completed his Autobiography of an Idea in 1924, the year of his death.

The American Institute of Architects posthumously awarded Louis Sullivan its prestigious Gold Medal in 1946.

Louis Sullivan’s life is an odd story of a hero. While his artistic output displayed his unique talents in design, ornamentation, and architectural structure, his lifestyle and noted caustic personality reflected his acute sensitivity to layers of personal suffering, both professionally and financially. How much of this could be attributed to his suppressed homosexuality can only be answered by the man himself, but it is a scenario often played out by LGBTQ individuals in an intolerant society every day.